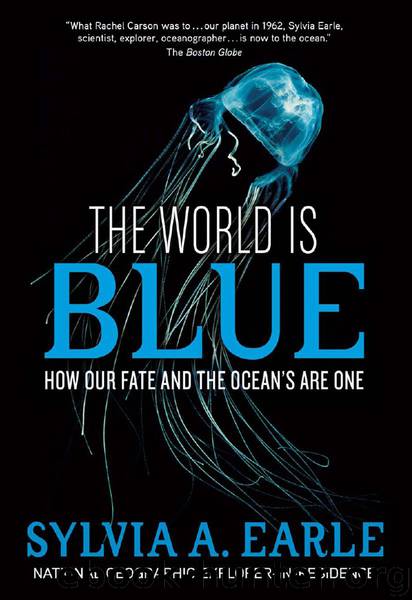

The World Is Blue: How Our Fate and the Ocean's Are One by Sylvia A. Earle

Author:Sylvia A. Earle

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Tags: Marine Biology, Life Sciences, Ecology, Oceanography, Nature, Marine ecology, Science, Environmental Science, Oceans & Seas, Nature - Effect of human beings on, Environmental Conservation & Protection, Marine pollution, Ecosystems & Habitats, Earth Sciences

ISBN: 9781426205415

Publisher: National Geographic

Published: 2009-09-29T14:00:01+00:00

Perversely spilled oil blackens Saudi Arabian marshes in 1991.

Worldwide, more than 4,000 rigs are now working in depths up to 1,830 meters (6,000 feet). The deepest offshore rig, Shell Oil’s Perdido Spar, is operating in nearly 2,400 meters (8,000 feet) of water in the Gulf of Mexico. Standing as tall as the Eiffel Tower 350 kilometers (220 miles) offshore, the giant spar supports 150 workers and two long-range helicopters, and supplies meals worthy of a four-star hotel.

Largely because the action occurs underwater, out of public view, little attention has focused on what actually happens on the ocean floor where drilling takes place, or what creatures are displaced by the thousands of miles of pipeline laced across the bottom to transport oil and gas once they are extracted. Until the concern about the burning of fossil fuels—coal, oil, and gas—as the basis for increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and thus global warming, ocean acidification, mercury contamination, and more, the greatest problem most people had with the development of offshore oil was the spilling of it.

THE ILLS OF SPILLS

A SeaWeb survey conducted by the Mellman Group in the mid-1990s found that “Americans believe the ocean’s problems stem from many sources, but oil companies are seen as a prime culprit. In fact, 81% of Americans believe that oil spills are a very serious problem.” Actually, spills can cause serious problems when they happen, and starting in the 1960s, they occurred often enough to arouse considerable public awareness—and ire.

Several mega-spills in the 1970s—Torrey Canyon, Amoco Cadiz, the uncontrolled gush of oil from Mexico’s Ixtoc I well—resulted in a spate of national and international regulations aimed at improving conditions for producing and shipping oil. Meanwhile, thousands of less conspicuous but insidious mini-spills continued from oily bilgewater released from ships, oily water drizzling down street drains, and millions of small leaks and spills from boats around the world.

A pivotal shift in public attitudes about oil spills came in April 1989 when the tanker Exxon Valdez split when it went aground in Alaska’s Prince William Sound, spilling 11 million gallons of Alaskan crude oil into the pristine waters. It dwarfed subsequent U.S. spills—the World Prodigy in Rhode Island; the Presidente Rivera in the Delaware River; the Rachel B/ Coastal Towing barge collision in Galveston Bay, Texas, and Mega Borg in the Gulf of Mexico; American Trader, and later, M/V Cosco Busan, both in California; and a large but unnamed spill in Tampa Bay in 1993.

With as much scientific detachment as I could muster, in May 1989 I tried to evaluate the reality of the spilled Alaskan oil as I skidded over oil-slick beach boulders, dug into oil-saturated sand, held barely moving oil-coated crabs, looked out over oilsheened waters, and listened to the wails of young otters, cleaned of oil but soaked in trauma as they huddled in holding cages at Valdez. My attempts to be open-minded collapsed as the horrendous toll continued to grow, and with it, a sense of despair about the nature of human

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4787)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4445)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4295)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3941)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3810)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3677)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3606)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(3448)

Hedgerow by John Wright(3340)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(3315)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(3298)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(3287)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3207)

Origin Story by David Christian(3185)

Water by Ian Miller(3166)

A Forest Journey by John Perlin(3057)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2915)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2848)

Forests: A Very Short Introduction by Jaboury Ghazoul(2825)